NSU Newsroom

SharkBytes

Horizons

This version of NSU News has been archived as of February 28, 2019. To search through archived articles, visit nova.edu/search. To access the new version of NSU News, visit news.nova.edu.

This version of SharkBytes has been archived as of February 28, 2019. To search through archived articles, visit nova.edu/search. To access the new version of SharkBytes, visit sharkbytes.nova.edu.

NSU Researcher to Help Map Genome of Russian Citizens

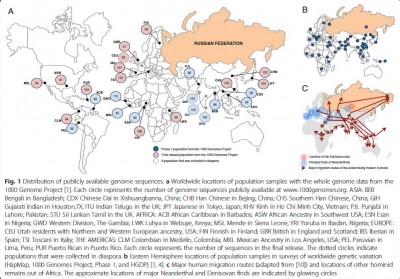

The list of countries and geographic regions that have been the subject of national population genome projects is extensive: the United States 1,000,000 genomes initiative; United Kingdom 100,000 Genomes project; Asia genomes; China; The Netherlands; and Qatar Genome Projects, to name just a few. All are committed to whole genome sequence from thousands of their citizens. In fact, nearly the entire globe is playing a role in human genome research by providing openly available whole genome sequences of tens of thousands of volunteers.

The list of countries and geographic regions that have been the subject of national population genome projects is extensive: the United States 1,000,000 genomes initiative; United Kingdom 100,000 Genomes project; Asia genomes; China; The Netherlands; and Qatar Genome Projects, to name just a few. All are committed to whole genome sequence from thousands of their citizens. In fact, nearly the entire globe is playing a role in human genome research by providing openly available whole genome sequences of tens of thousands of volunteers.

Yet one vast region that occupies 1/10 of the earth’s landmass and 1/50 if its people has yet to participate in any such project – the Russian Federation. All that is about to change, thanks to a consortium of genetics researchers from Russia with some advice and urging from Stephen J. O’Brien, Ph.D., a professor and research director at Nova Southeastern University’s Halmos College of Natural Sciences and Oceanography.

“When you look at a world genome representation map, there’s a huge swath of space that is absent from this research,” said O’Brien. “Mapping human genome diversity has enormous implications for medicine as well as natural human history, but we need to ensure that all areas of the world are part of the research. The ‘Genome Russia’ Project’s goal is to fill a large void in our understanding of human genetics.”

O’Brien said that the idea behind the new research is to create a “global reference resource” of genomes from 2,500 people from across Russia that will annotate all human genetic variation and provide a new way for disease variant discoveries. That’s why it’s so important to bring the Russian people into the fold – the rich background of genomic diversity in this part of the world is key to creating a more comprehensive DNA fingerprint of the human genetic mystery.

O’Brien splits his time between NSU and the Theodosius Dobzhansky Center for Genome Bioinformatics in St. Petersburg, Russia, which he directs and founded in early 2012; he is coordinating a large consortium that will be undertaking this important work.

The Genome Russia Consortium wants to study the genetic make-up of Russian citizens because the area played a role throughout human history in terms of migratory patterns for our species. Our most ancient ancestors moved through the area we call Russia toward many areas, including Northern and Central Europe, as well as the northward and westward expansion of the Indo-Europeans and the Uralic people, the westward expansion of the Turkic people, and centuries of ad-mixture between them. The pre-historic migration diaspora have created a complex patchwork of human diversity that is today’s Russia and somewhere hidden in Siberia reside the ancestral roots for modern Native Americans.

In the way more distant past around 30,000-45,000 years ago, gene exchange likely occurred between modern humans, Homo sapiens and the Neanderthal and Denisovan populations they encountered. The genetic contribution of the Neanderthal has not been well studied beyond Western Europe; nor has that of the Denisovan for South East Asia, despite their physical remains being unearthed in Siberia. Russian populations very likely contain ancestral components that aren’t easily found in other genomic databases. O’Brien and his team suggest that’s why Russia needs a national genome project on its own.

“Without this information, we won’t have a truly comprehensive genomic picture of human existence,” O’Brien said. “We’ll be venturing into uncharted territory, and for research scientists that’s always exciting.”